The church in history

History as we know it was “invented,” so to speak, as a product of the Renaissance and the beginning of true scientific inquiry of all kinds. It’s not as though no serious attempts at history were made before but that, but until the principles of scientific history were enunciated, accounts of the past tended to be less than reliable as matters of fact. Scientific investigation of the past, which relies on documentation, verification and corroboration, was simply not done as a matter of general principle before the development of critical philosophy in the 17th and 18th centuries and the formal scientific method in the 19th. The critical study of history, in other words, is relatively recent invention, while Christian history – indeed, most of world history – is ancient.

Christian scripture, then, may be regarded as of historical interest as sources of information, but nothing in the canon can be properly understood as “history,” because it is not verifiable and can not be corroborated. In a sense, then, the very existence of Jesus of Nazareth is open to question as a matter of scientific inquiry. There is no record of his having lived in first-century Palestine, except the gospel accounts, which are not historical records but theological explanations of the meaning of Jesus’ life. Scientifically historical evidence would be a neutral record of, say, Jesus’ having been executed, but no such record exists now, if it ever did. This lack of historical documentation is just as true for other ancient personages as it is for Jesus. Reconstructing the past from archeology and ancient written records, such as Egyptian hieroglyphics, is an enormously complex and challenging task. Quite simply, the church has been “in history” longer than the history of scientific history itself, and that poses huge problems for our understanding of the early church.

Early-church documents are few and archeology rare. Luke-Acts was conceived as a kind of history, but little of it can be corroborated scientifically. It was the Christian community’s last attempt that has survived since the first century CE to give an account of the community’s development. It ends before 65 CE, and it was written 10 to 20 years after the events it recounts. With the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 and the deaths of all or most first-generation Christians not long thereafter, church history enters a tunnel, so to speak, and doesn’t emerge from it with any clarity for almost 200 years. There are sporadic surviving documents, but not nearly enough to get an accurate picture of this critical period – the community’s development from a Jewish sect to a free-standing religious movement that, in the fourth century, became an imperial state religion.

We know from fragmentary evidence that Christian communities formed around bishops and their deacons, and that they tended to be hierarchical and exclusive. Initiation was a long process, up to three years and less for purposes of instruction than moral scrutiny. The Christian community set itself apart from the world with high expectations of its members that they be chaste, law abiding, peace-loving and loyal. (This was especially important in times of persecution.) The presbyterate emerged as the church grew. “Station church” congregations were established as missions from a bishop’s principal congregation, and presbyters were ordained to oversee them. Each Sunday, deacons were sent to station churches with bread from the bishop’s celebration of the Eucharist to signify that congregation’s unity with its founding bishop.

Baptism was an annual celebration on the eve of Easter. The norm was adult baptism by immersion. Children were baptized incidentally with their parents, but it was not customary to baptize newborns or children by themselves. The rite we now call confirmation, signified by anointing with oil, was the finale of the baptism ceremony. Deacons actually immersed the catechumens – women deacons immersed women – and as the nude, newly-baptized people emerged from the baptismal pool, they were vested in white garments like an alb. Soaking wet, they were anointed by the bishop, and then began the Easter Vigil, which lasted until daybreak. As the sun’s first rays cross the skies, a deacon chanted, “Alleluia, Christ is risen,” and so the Eucharist began.

The structure of church government seems to have mimicked Roman administration. Our term “diocese” is from the Greco-Latin term for a secular governmental unit; which, charmingly enough, comes from a Greek idiom for “keeping house.” The church, in other words, grew rapidly and so did its administrative apparatus. Persecution by the Roman state was sporadic and localized, although some general persecutions did occur; e.g., that of the emperor Diocletian, probably the worst of all, which began in 303. Those laws were abolished by the Edict of Milan in 313, which decreed religious tolerance, and by 324, with Constantine as sole ruler of the empire, Christianity had become the empire’s state religion.

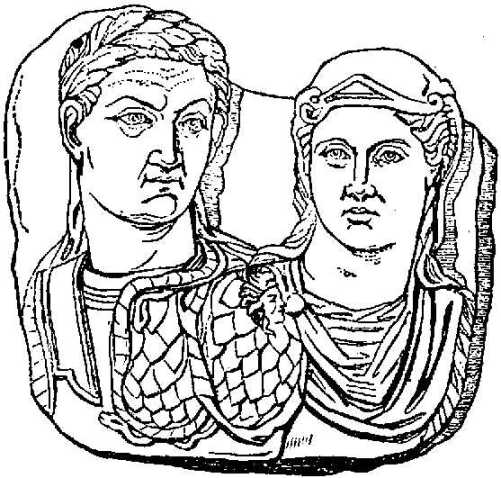

Constantine had been converted to Christianity in 312 by a dream before the battle of Milvian Bridge, in which the emperor was told he would conquer his enemies by putting the sign of the cross on his soldiers’ shields. His outnumbered army won the battle. Constantine, however, was not baptized until he lay on his deathbed in 337, because he knew it was unlikely that he could live up to the church’s high moral standard.

Things changed dramatically for the church when it became a state religion. Its bishops became state officials entitled to certain emblems of office; miters, for example, the headgear worn to this day by all Roman Catholic and Orthodox prelates and even some Anglicans; and they were heralded through the streets in procession with incense and lighted tapers. Church communities became inclusive, because now it was an obligation of Roman citizenship to belong to the state church. Matters of theology and church order became matters of state and of keen interest to the emperor, who demanded uniformity and conformity. The church had gone from being persecuted and politically powerless to being politically significant and powerful.

It’s probably not a good thing that the Christianity became a state religion, but now it’s hard to imagine our history without it in that pivotal role. We can not imagine what might have occupied that cultural niche had it not been the Roman Catholic Church in the west and the Eastern Orthodox churches in the east. That split, by the way, occurred formally in 1054 and had been a long time coming – about 187 years. To our eyes, the controversy was the relatively minor matter of the custom of inserting a clause (actually, a single word in Latin) into the Nicene Creed asserting that the Holy Spirit “proceeds from the Father and the Son.” (Latin, filioque) The custom, tolerated in most churches, was condemned by Orthodox councils in the east and affirmed by Roman Catholic councils in the west. Yes, it’s a lot more complex than that, but by 1054, the Great Schism had been accomplished. Councils in 1274 and 1439 seemed to iron out the problem, but the schism still remains.

Not surprisingly, and very early on, Christian ascetics – people who pray a lot and very seriously – began fleeing Christianity’s urban centers to seek God in the wilderness. They found the institution corrupt and they tended to believe that the governing apparatus, with its formality and mass appeal, did more to hinder than cultivate spirituality. These ascetics became known as the mothers and fathers of the desert. Anthony of the Desert, who lived from about 251 to 356, is acknowledged as the father of this movement. He was not the first – Ama Thecla is a second-century desert mother – but Anthony is certainly the most well known. His life is a kind of paradigm for this facet of the Christian story. (Note: Desert ascetics also were known in non-Christian cultures. A first-century Jewish philosopher, Philo, once described a community of pagan “therapeutae” [from the Greek for “cure” or “worship”] living near Alexandria.)

Anthony was born rich in Alexandria, inherited his parents’ estate and the care of his younger sister. At age 34, he took seriously Jesus’ saying that true disciples sold their property, gave it to the poor and took up their cross to follow him. Anthony cashed out, left his sister in the care of a community of religious women and, after spending some time with a local hermit, walked about 60 miles into Egypt’s western desert. He sequestered himself in several places over the years – caves, a tomb, an old Roman fort – and was widely regarded as a holy man, though he would permit no one to see him face to face. He consciously sought martyrdom during Diocletian’s general persecution, but the provincial governor, realizing his fame, refused to arrest him.

Disciples, meanwhile, had begun following Anthony, so he returned to the desert with them and founded a community that supported itself by making mats of rushes. Some of Anthony’s words of wisdom appear in a fourth-century life of Anthony written by Athanasius, among them: “Believe on the Lord and love Him; keep yourselves from filthy thoughts and fleshly pleasures, and as it is written in the Proverbs, be not deceived ‘by the fullness of the belly.’ Pray continually; avoid vainglory; sing psalms before sleep and on awaking; hold in your heart the commandments of Scripture; be mindful of the works of the saints that your souls being put in remembrance of the commandments may be brought into harmony with the zeal of the saints.”

Desert spirituality represents a significant strand of Christian tradition. It’s a kind of puritanism but with a small “p,” because it’s not historically related to the 17th-century Puritan movement in England. Both types, though, small and capital, seek a kind of purity that rejects institutional excess, whether it be of government, theology or liturgical practice. Puritanism of all types purports to seek a “return to basics” that strips away what it considers things superfluous to the essential matter of ________ (fill in the blank).

Desert ascetics sought an unmediated encounter with God and so fled the cities and urban churches filled with adherents in name only. They sought the silence of the desert, its uncluttered landscape, its stark reality. The 17th-century Puritans wanted a church without candles, vestments, incense and what it regarded as superstition, such as the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. Most of all, it wanted to be free of conformity with a state church that hadn’t done enough to reform itself. In any case, the idea of “pure Christianity” has loomed large in all reform movements from the beginning. The first great theological debate in church history was about purity; i.e., whether uncircumcised gentiles ought to be admitted to Christian community solely on the basis of their baptism. There has never been a century without controversy in all Christian history.

Leave a comment